Deliberate practice

Deliberate practice has been demonstrated to be an effective method for achieving expert performance in a variety of competencies. There is a strong correlation between the amount of time a student spends not just practicing, but doing deliberate practice, and the student's long-term outcomes.

Playing a musical instrument, such as the violin, has a long history of instruction and practice. The best violinists have spent countless hours of solitary practice and the majority of their practice time in their teen and pre-teen years.

Maker education revolution

Conventional education is struggling to provide the learning environment necessary to help raise the future innovators, problem solvers, and entrepreneurs that advanced societies need. Maker Education offers a model for education in the 21st century.

“Failure is instructive. The person who really thinks learns quite as much from his failures as from his successes.”

— John Dewey

Being really good at something is often assumed to be a special gift. Whether it is great skill in playing a musical instrument, being fast in completing arithmetic calculations, remembering phone numbers and people’s names, or being a great programmer or engineer; it must be something that such people are born with. When someone achieves a high level of performance, high enough to be noticed by others, the layperson will assume that the high performer was lucky enough to be born with some kind of natural aptitude to be great at this particular task.

While the jury for the portion of ones success that can be attributed to nature versus that earn by nurture and hard work, we often fail to acknowledge the many years of purposeful and continuous practice that such people have invested in their specialty.

Research done by scientists like Anders Ericsson has documented the process that a person has to follow, over a long period of time, that is necessary for achieving a high level of performance.

Ericsson calls this “deliberate practice”.

In deliberate practice, a person pursues specific goals, set either by themselves or by a mentor or instructor, that are specially designed to improve a specific aspect of their performance.

Deliberate practice has been shown to be a way of achieving expert performance in many competencies, such sport, chess, or playing musical instruments. We can learn a lot from it and apply it in many other areas in order to significantly increase the practitioner’s skill level.

In this chapter, I will explain how deliberate practice can be applied in learning.

Let’s look at an example from Ericsson’s research (1).

Ericsson and his collaborators wanted to understand how some of the best violinists in the world achieve their level of performance. To do so, they followed a group of music students at the Berlin University of the Arts, an internationally highly regarded institution for both its pupils and its teaching staff. Famous conductors and composers, like Otto Klemperer and Kurt Weill, are graduates of this university.

For the purpose of this research, Ericsson focused on the violin students because of the university’s reputation of producing world-class violinists. Playing a musical instrument, like the violin, has a long-established method of teaching and practising, and objective measures of performance. These are important characteristics for researchers because they allow them to derive conclusions that are free of externalities, like the environment and luck.

It is very hard doing research like this in areas such as business or team sports. For example, in a game like football, it is very hard to find objective measures of performance. In football, the top-scorer’s performance can be the result of both his ability to score, and his teammates’ ability to pass the ball to him at exactly the right time and place, as well as create the conditions in the game to allow for scoring to take place.

The researchers started by separating their student subjects into three groups based on information they received from their teachers. The first group included super-star students. These students showed characteristics that indicated they would graduate to be the world’s top performers, the best in the world, the future orchestra soloists. The second group included students that while very good, were not top performers. Finally, the third group included students from the music education department, who were on track to becoming school music teachers, not orchestra performers. Although they were very good at playing the violin, at this stage they were not as good as the students in the first two groups.

The violin is an instrument that requires a lot of practice. A single note can be played in many different ways, and even the way that a musician holds the instrument will influence the way that it will sound. Because all of the students in the study spent the same amount of time with their instructor, the researchers were able to measure how much of their improvement in skill level could be attributed to the student them self. And most of them had already been practising since around the age of eight. At the time of the research at the university, they had been practising for almost ten years.

The researchers conducted interviews, analysed diaries and witnesses numerous practice sessions. What the researchers found was that the best violinists had spent, on average, a significantly higher number of hours in solitary practice than the second group had. While the music education students, by the time they entered the University of the Arts, had spent 3,420 hours on solitary practice, the better ones had spent 5,301 hours and the best had practised 7,410 hours. All of them were clearly working hard. Even the music education students had practised for thousands of hours more than a person who might play the violin for fun. But the best of them had put in far more hours than anyone else.

Another interesting outcome from this research was that for the best violin students, the bulk of the practice time had been completed in their teen and pre-teen years. This is important because these years are particularly challenging for building any kind of skill due to the various competing interests: sports, hanging out with friends, partying, etc.

A similar study involving middle-aged violinists who work at the prestigious Berlin Philharmonic and the Radio Symphonie Orchester Berlin also agrees with this finding: practising before the age of 18 is an extremely important factor that can determine career outlook, at least for a violinist.

The researchers discovered a similar pattern in other areas, such ballet, chess, mathematics, and many more.

When it comes to using lessons from Ericsson’s deliberate practice research in school settings and in particular in the context of Maker Education, we must remember that deliberate practice, in general, suggests that there is a strong correlation between the amount of time that a student spends not just practising, but doing deliberate practice, and the long-term outcomes for that student. However, the experiments were conducted in areas of knowledge and skill in which there was a long history of teaching, during which the teaching methods were fine-tuned over time to enable students to learn from best practices.

The violin, for example, has been taught for hundreds of years, and the methods of teaching have changed dramatically over the years. As a result, an average violinist today is far better in every respect when compared to legendary violinists from the eighteenth century.

In Maker Education, the areas of knowledge that are being taught tend to be things like electronics, 3D design and manufacturing, algebra, woodworking, metalworking, and programming. Most of these are modern disciplines with a lot less history of teaching in comparison to the violin or chess.

But the fact remains that early age deliberate practice can make a significant difference to the skill level that the student can reach.

How can this be? In deliberate practice, a teacher is responsible for helping the student to increase his or her performance in specific areas by prescribing practice activities. In Maker Education, the mentor is responsible for this. The prescribed activities have a goal, but in the spirit of constructionism, they also contain a high level of freedom for the student to choose their own path in achieving that goal.

Many lessons on how top performers achieve their skill come from Ericsson’s deliberate practice research. Some of these lessons are particularly useful in a Maker Education context:

* In deliberate practice, the skills taught are such that they have already been achieved by others. A mentor will not ask a student to implement a robot function that he knows is not possible with current technology or established techniques.

* Practice takes place outside the student’s comfort zone. This theme comes up repeatedly in research. Whether we are looking at the world’s top performers or music education teachers, their practice is not considered to be fun, but stressful. The best students will tolerate this stress because they can measure their improvement. They practise with the goal in mind, not for the fun of practice. The satisfaction they receive from this constructive stress stems out of achievement that they feel. Just like fun, satisfaction stemming from achievement can be powerfully motivating.

* Deliberate practice requires the student’s full attention. The student must focus and become absorbed in their practice. It is not enough to blindly copy the instructions in a textbook or the instructions of the teacher.

* Deliberate practice requires fast feedback. In the case of Maker Education, for example, this feedback comes from the tangible artefacts that the student works on. An incorrect wiring will result in a circuit that is not functioning. This is the feedback that the student has to evaluate and rectify. A corrected connection will result in a working circuit; this is new feedback that acknowledges whatever the student did to deal with the situation worked.

* In deliberate practice, the student almost always builds and improves on previously acquired skills. The improvement occurs by the student and the teacher identifying a specific area for improvement, and designing and implementing exercises that specifically address that area. As a result, it is very important for students to have a very good grasp of the fundamentals in their area of study. Without this, deliberate practice will not be possible.

Can Maker Education provides an environment in which deliberate practice can take place? Absolutely! The responsibility for this is with the mentor, who must constantly offer the student opportunities for improvement, and constructive feedback.

References

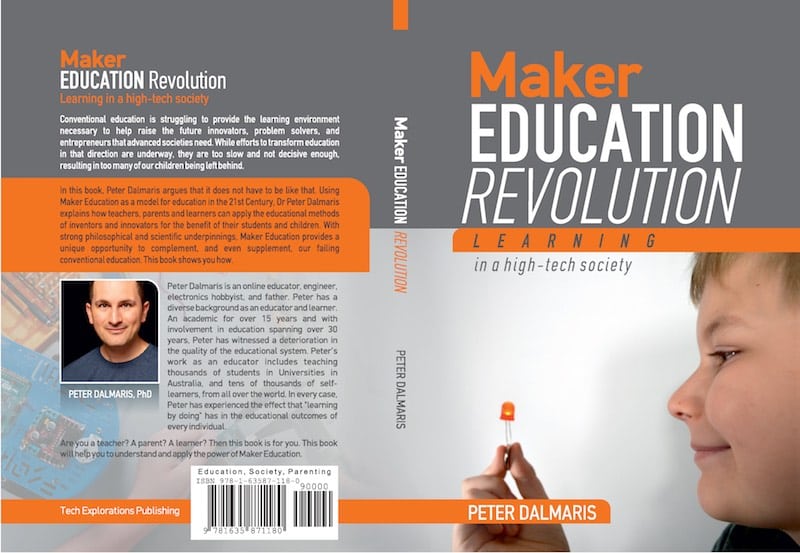

Maker Education Revolution

Learning in a high-tech society.

Available in PDF, Mobi, ePub and paperback formats.

Using Maker Education as a model for education in the 21st century, Dr Peter Dalmaris explains how teachers, parents, and learners can apply the educational methods of inventors and innovators for the benefit of their students and children.

Jump to another article

1. An introduction

2. A brief history of modern education

An education in crisis, and an opportunity

3. An education system in crisis

4. Think different: learners in charge

5. Learning like an inventor

6. Inventors and their process of make, test, learn

7. Maker Education: A new education revolution

What is Maker Education?

8. The philosophy of Maker Education

9. The story of a learner in charge

10. Learners and mentors

11. Learn by Play

12. Deliberate practice

13. The importance of technology education

14. The role of the Arts in technology and education

15. Drive in Making

16. Mindset in Making

Maker Education DIY guide for teachers, parents and children

17. Learning at home: challenges and opportunities

18. Some of the things makers do

19. The learning corner

20. Learning tools

21. Online resources for Maker learners

22. Brick-and-mortar resources for Maker learners

23. Maker Movement Manifesto and the Learning Space

An epilogue: is Maker education a fad or an opportunity?

24. Can we afford to ignore Maker Education?

25.The new role of the school

We publish fresh content each week. Read how-to's on Arduino, ESP32, KiCad, Node-RED, drones and more. Listen to interviews. Learn about new tech with our comprehensive reviews. Get discount offers for our courses and books. Interact with our community. One email per week, no spam; unsubscribe at any time