Drive in Making

Motivation can be internal, such as the need to survive and be safe, or external, such as monetary rewards and social prominence.

Both drive and a growth mindset are naturally present in children, according to research. Maker Education focuses on nurturing and enhancing our natural desire to learn for the sake of learning.

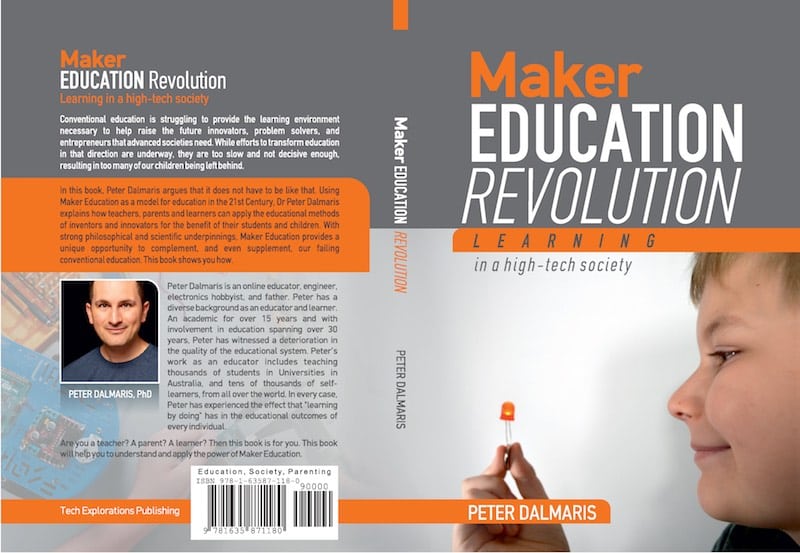

Maker education revolution

Conventional education is struggling to provide the learning environment necessary to help raise the future innovators, problem solvers, and entrepreneurs that advanced societies need. Maker Education offers a model for education in the 21st century.

“Steve Jobs, Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg didn’t finish college. Too much emphasis is placed on formal education - I told my children not to worry about their grades but to enjoy learning.”

— Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Research in human performance over the last 50 years has shown something that surprised everyone in the business of getting people to work harder, faster and better.

In the first instance, scientists discovered that while people respond to external motivators, like monetary rewards, praise and status, in the short term, these motivators quickly lose their efficacy. When these motivators wear out, people tend to find it hard to maintain a high level of performance. Instead, what works much better is what the scientists called ‘drive’ (1). Drive is an internal, intrinsic motivator that pushes people to seek novelty, challenges, and the desire to explore, learn and improve their capabilities. But drive is more fragile than external motivators; it needs the right environment to survive and thrive.

In the second instance, researchers found that people create mental models of themselves in the world that are critical in shaping how they navigate through it, via their actions and behaviours. In general, there are two broad models: in the first one, people believe that their skills and abilities are fixed. No amount of work will change anything. Setting high goals is pointless. This is the fixed mindset. In the second one, people believe that their skills and abilities are not fixed. Through hard work and planning it is possible to improve every aspect of their performance. Setting high goals is not only pointless, but an obvious behaviour of someone who truly believes they can achieve them. This is the growth mindset.

Research shows that both drive and the growth mindset are naturally present in all of us in childhood (2). Somewhere, during the process of schooling and engaging with society as adults, many of us lose them both. Even then, though, both can be regained and used to transform lives and careers in a powerful and meaningful way.

Let’s look at drive, first (and examine the role of the mindset in the next chapter). Harry F. Harlow, a professor of psychology at the University of Wisconsin in the 1940s, was interested in the behaviour of primates. In an experiment in 1949, he used rhesus monkeys to conduct a two-week experiment on learning. He created a simple mechanical puzzle that is easy for humans to solve. His expectation was that the monkeys would find it harder. The researchers placed the puzzle in the monkeys’ cage and waited to see their reaction. What happened was very interesting. Without any external motivators, like food or prompting, the monkeys immediately became interested in the new object in their environment and began playing with it. They seemed focused, determined and to be genuinely enjoying the experience. It took them around 60 seconds to solve the puzzle.

Up to that point, in psychology, the accepted theory of motivation told a different story. Motivation can be either biological in nature, like the need to survive and be safe, or external, like the promise of monetary rewards and social prominence. This was the premise on which the Industrial Revolution was built, in which the factory system relied on monetary compensation to incentivise people to do menial and often dangerous work.

But what Harlow found, at least in primates, was that there is another force, drive, that is just as powerful, and perhaps even more so. Drive is what made the monkeys solve the puzzles. They did so for personal gratification, because they found it interesting and derived joy in doing so.

How might ‘drive’ translate to humans? Many years later, Edward Deci, who in 1969 was a Carnegie Mellon University graduate student, became interested in Harlow’s research. Harlow never continued his research with human subjects, and Deci decided to do just that. He devised an experiment in which two groups of students were given a challenge in the form of Soma puzzle cubes. The experiments were designed to see how much of the interest that the subjects showed to solving the puzzles was due to their intrinsic motivation (i.e. their drive, how much they enjoyed solving a puzzle) versus how much was due to external motivators, and in particular in the form of monetary rewards (3).

What Deci found was incredible, even so many years later. Here is what happened.

The experiment lasted for three days. In the first day, both groups were given the puzzles, and asked to reproduce a particular pattern, with no reward. At some point, the researcher would leave the room pretending to need to transfer data to a computer, and asked the students to do whatever they wanted in the next eight minutes. They could choose between doing nothing, reading one of the magazines or newspapers left on the table, or continuing to play with the puzzles.

On the first day, where there was no reward offered for solving a puzzle, students in both groups behaved in a similar manner. They continued to be interested in the puzzle for two or four minutes, before they lost interest and did something else.

On the second day, group A was offered a monetary reward for each puzzle solved, while group B was not offered a reward. After a couple of sessions with the researcher in the room, the researcher, just like on the first day, left the room pretending to have to copy the data in a computer, and left the students alone for eight minutes. Again, the students were told that they could do anything they wanted during this time. How did they behave? As common sense expected, students in group A seemed to be much more interested in the puzzles, spending more than five minutes messing around with them. The behaviour of the students in group B was the same as on day one. Why did students in group A show such strong interest? Perhaps they wanted to improve their chances for earning more monetary rewards on day three?

On day three, the experiment was repeated, but this time students in group A were told that there was no more money to be won. During the eight minutes of ‘break’ students in group B, who had never been paid to solve a puzzle, actually spent a bit more time with it. Perhaps they were getting fond of it and wanted to try out or learn new patterns. But the students in group A, that had been paid in the experiment the day before, spent significantly less time with it: a minute less than the time they spent on the puzzle on the first day of the experiment.

This suggests that even though all subjects enjoyed this task the same before an external reward was offered, the level of enjoyment was influenced in a negative way once a reward was offered and then removed.

Deci concluded that “When money is used as an external reward for some activity, the subjects lose intrinsic interest for that activity” (3). Often, external motivators like money not only don’t help in achieving a better outcome, but they make it less likely to achieve a better outcome.

One of Deci’s conclusions of these experiments is that humans have an “inherent tendency to seek out novelty and challenges, to extend and exercise their capacities, to explore, and to learn.”

This is particularly important in the context of the Maker Movement since drive seems to be the core motivation for why makers do what they do.

In pure making, we cultivate the intrinsic drive that the rhesus monkeys and human experiment subjects had for doing something for the pure pleasure of doing it. It is why Wikipedia succeeded while Microsoft’s Encarta didn’t. It is why Linux runs the Internet today. It is why the Open Source movement has shaped much of the development of the Internet and the information superhighway.

In these examples, thousands of individuals worked and still work for long periods of time against the common perception that humans respond to monetary and other external rewards. The authors of Wikipedia articles, the authors of the code in Linux, Apache and SQLite are not compensated with money. In fact, they probably ignore money-making opportunities. Instead, they are following their internal drive to create something bigger than themselves, something deeply meaningful.

Maker Education is about the process of cultivating and strengthening our intrinsic drive to learn for the sake of learning, and make for fun. The process is more important than the tools, technologies and by what specifically it is that we make. This is a classic case of ‘the journey is more important than the stopovers’. Even the destination is not important, since it is different for each one of us.

References

- Pink, D. H. (2011). Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us.

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York: Random House.

- Deci, E. L. (April 01, 1971). Effects of Externally Mediated Rewards on Intrinsic Motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 18, 1, 105-115. https://txplo.re/1a3c07.

Interesting viewing

Maker Education Revolution

Learning in a high-tech society.

Available in PDF, Mobi, ePub and paperback formats.

Using Maker Education as a model for education in the 21st century, Dr Peter Dalmaris explains how teachers, parents, and learners can apply the educational methods of inventors and innovators for the benefit of their students and children.

Jump to another article

1. An introduction

2. A brief history of modern education

An education in crisis, and an opportunity

3. An education system in crisis

4. Think different: learners in charge

5. Learning like an inventor

6. Inventors and their process of make, test, learn

7. Maker Education: A new education revolution

What is Maker Education?

8. The philosophy of Maker Education

9. The story of a learner in charge

10. Learners and mentors

11. Learn by Play

12. Deliberate practice

13. The importance of technology education

14. The role of the Arts in technology and education

15. Drive in Making

16. Mindset in Making

Maker Education DIY guide for teachers, parents and children

17. Learning at home: challenges and opportunities

18. Some of the things makers do

19. The learning corner

20. Learning tools

21. Online resources for Maker learners

22. Brick-and-mortar resources for Maker learners

23. Maker Movement Manifesto and the Learning Space

An epilogue: is Maker education a fad or an opportunity?

24. Can we afford to ignore Maker Education?

25.The new role of the school

Last Updated 1 year ago.

We publish fresh content each week. Read how-to's on Arduino, ESP32, KiCad, Node-RED, drones and more. Listen to interviews. Learn about new tech with our comprehensive reviews. Get discount offers for our courses and books. Interact with our community. One email per week, no spam; unsubscribe at any time