Learn by Play

A term used in education and psychology to explain how children make sense of the world is "learning through play." Children can explore, identify, take risks, and comprehend the world around them through play.

Playing as a learning instrument is almost completely overlooked in adult education. The value of play in learning is emphasised in Montessori, Reggio Emilia, and Maker-style education. Allowing children to learn through play teaches them to find and confidently follow their own paths.

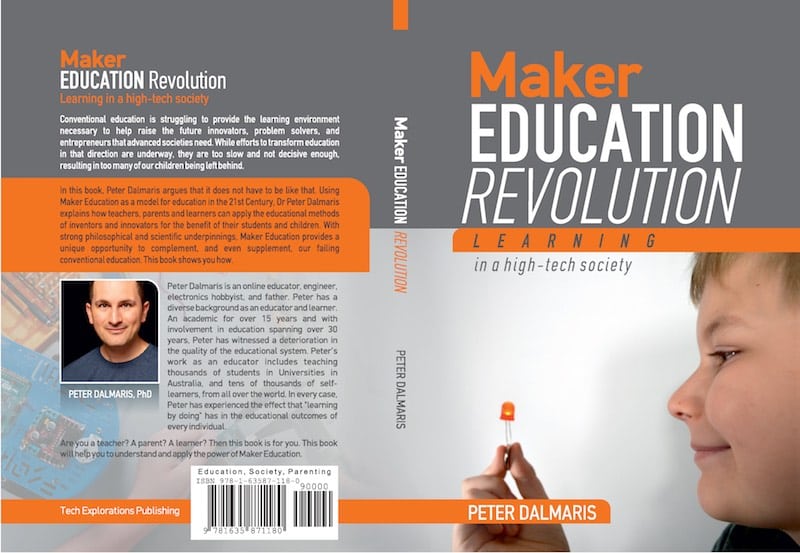

Maker education revolution

Conventional education is struggling to provide the learning environment necessary to help raise the future innovators, problem solvers, and entrepreneurs that advanced societies need. Maker Education offers a model for education in the 21st century.

“The goal of early childhood education should be to activate the child’s own natural desire to learn.”

— Maria Montessori

In Maker style education, playing, making and learning are intertwined into one.

I often use the word “play” in place of making or learning because very often it really is no different.

The objective of a Maker Education is to help learners become self-reliant, confident, creative and innovative individuals. Playing is about enjoyment and recreation, it has no other purpose. Certainly, it has no practical purpose.

What does research show about playing and learning? ‘Learning through play’ is a term used in education and psychology to describe how children make sense of the world around them, and develop their social, cognitive and emotional skills that they will need as adults. Through play, children interact with other people, real or imaginary, objects and their environment. In the course of play, children are challenged to solve problems and both to adapt and influence or change their environment.

There is strong evidence to suggest that play affects brain development, and stimulates improved memory skills, language and behavioural development (1).

There is also a large amount of evidence that play is associated with intellectual and cognitive benefits in children (2). Play allows children to explore, identify, take risks and understand the world around them, some of the core skills that we recognise in Makers and well developed adults.

Despite the evidence, the role of playing in learning is often underestimated, especially as children grow older. Playing as an instrument for learning is almost completely ignored in adult education.

Successful learning through play involves five elements (3):

- Play must be pleasurable and enjoyable.

- Play must have no extrinsic goals; there is no prescribed learning that must occur.

- Play is spontaneous and voluntary.

- Play involves active engagement on the part of the player.

- Play involves an element of make-believe.

How is play different to work? Apart from the five elements outlined above, a major distinction is that work is usually externally directed while play is mostly self-chosen activity with no specific goals. Play resembles the exploration of the unknown, while work has specific utility and specifications that must be met.

This difference is important as it helps educators avoid the mistake of creating a play activity that in reality is work. For example, a common tool for trying to help people memorise words in their effort to learn a new language is the use of flash cards. Even though educators often describe this activity as “let’s play flash cards”, in reality they are prescribing work. The activity has very little room for exploration, has a specific goal and is externally prescribed.

Over the last forty years, a lot of research has been published to help us understand the relation between playing and learning. This research has also led to play-based learning programs that have been used with children for even longer than that.

For example, the Montessori Method has been used since its founder, Maria Montessori, opened her first classroom in 1907. Montessori schools follow a constructivist approach in which self-directed play is at the core of the learning process. Children are given ample uninterrupted blocks of time, usually around three hours, to engage in an activity of their choice from a range of possible activities. The children can move around freely in the classroom, interact with other children and with the teacher. The teacher’s role is to observe, facilitate and assist if necessary.

Another method that emphasises play in learning is the Reggio Emilia approach. Like Montessori, Reggio Emilia emphasises the importance of self-directed learning, the ability to freely explore the real world around them, the interaction with other people, and also the importance of expression. A core principle of the Reggio Emilia approach is that “children must have endless ways and opportunities to express themselves”.

Other similar approaches to learning in which play is emphasised include Steiner/Waldorf Education, Sudbury Schools, the Summerhill School in Suffolk, England, and Charlotte Mason schools, to name but a few.

Why are these schools so popular among parents and students? How do they relate to the Maker-style Education?

The common element between them and Maker-style Education is that children are encouraged to play as a pedagogical way of supporting their learning experience. Facilitating play as a way to learn accustoms children to find and confidently follow their own paths. This has significant consequences in adult life.

Take the example of a five-year-old child presented with a set of wooden blocks.

In the first instance, the teacher says to the child: “I will show you how to create a tower using these blocks. After I finish, you can try.” The teacher proceeds to carefully place a large block on the table, followed by a slightly smaller block on top of it, followed by another, smaller block on top of that. In the end, the teacher places the final, tiny block at the top of the tower, and informs the student that the tower is now ready. “Your turn!”

In the second instance, the teacher says to the child: “How about you take these blocks and make a tower as high as you can!” No demonstration, no building instructions, no specifications. Just an abstract objective that the student is free to interpret and act on using their prior knowledge of what a tower is, and some experience in building with blocks, if any at all.

In the first instance, we have a work assignment. The young child, not yet trained in following instructions, will start with the intention of building a tower like the one that the teacher demonstrated, but soon he will become sidetracked. He might go on building an object that is closer aligned to his own ideas of what a tower looks like, or give up completely and go find something to play with (as opposed to completing the work that was assigned to him by the teacher). The teacher will try to insist that the student completes the assignment, and might even demonstrate again how it should be done.

In the second instance, the student is in play mode. He tries different configurations, each time rearranging blocks so that the structure becomes more stable and taller than the previous iteration.

Did the student in the second instance enjoy his activity with the blocks? Yes! He was focused and engaged, he was living for the moment. His mind and hands created an outcome that embodied the learning that he achieved in the process. He made structural corrections, which taught him the value of iteration and gradual improvement. He developed his own quality assurance tests, and he understood why a new configuration was better than an old configuration.

While learning by playing is certainly not suitable for achieving every learning objective, it is a powerful approach for building those traits and personal characteristics that can help people respond well to high stakes and stressful learning experiences, whether they are in their older years of schooling, professional development, or life in general.

Play for adults is as important as it is for children. In a way, this is why adults tend to have hobbies. Hobbies allow adults the opportunity to escape their structured, externally controlled lives and indulge in a self-chosen and self-directed activity. Hobbies give adults the opportunity to refresh their mind and body, and enjoy many other benefits: increased levels of energy, improved creativity, better teamwork, stress-free interaction with other people, and so on.

In Maker Education, play is an essential tool to learning, just as it is for so many other schools, philosophies and learning approaches.

References

- Lester, S. & Russell, S. (2008). Play for a change. Play policy and practice: A review of contemporary perspectives. Play England, https://txplo.re/pfc

- Bodrova, E. & Leong, D. J. (2005). Uniquely preschool: What research tells us about the ways young children learn. Educational Leadership, 63(1), 44-47. https://txplo.re/a8145f

- Einstein Never Used Flash Cards, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, Roberta Michnick Golinkoff, Rodale Inc., ISBN 978-0-08-023383-3

Interesting readings

Maker Education Revolution

Learning in a high-tech society.

Available in PDF, Mobi, ePub and paperback formats.

Using Maker Education as a model for education in the 21st century, Dr Peter Dalmaris explains how teachers, parents, and learners can apply the educational methods of inventors and innovators for the benefit of their students and children.

Jump to another article

1. An introduction

2. A brief history of modern education

An education in crisis, and an opportunity

3. An education system in crisis

4. Think different: learners in charge

5. Learning like an inventor

6. Inventors and their process of make, test, learn

7. Maker Education: A new education revolution

What is Maker Education?

8. The philosophy of Maker Education

9. The story of a learner in charge

10. Learners and mentors

11. Learn by Play

12. Deliberate practice

13. The importance of technology education

14. The role of the Arts in technology and education

15. Drive in Making

16. Mindset in Making

Maker Education DIY guide for teachers, parents and children

17. Learning at home: challenges and opportunities

18. Some of the things makers do

19. The learning corner

20. Learning tools

21. Online resources for Maker learners

22. Brick-and-mortar resources for Maker learners

23. Maker Movement Manifesto and the Learning Space

An epilogue: is Maker education a fad or an opportunity?

24. Can we afford to ignore Maker Education?

25.The new role of the school

Last Updated 1 year ago.

We publish fresh content each week. Read how-to's on Arduino, ESP32, KiCad, Node-RED, drones and more. Listen to interviews. Learn about new tech with our comprehensive reviews. Get discount offers for our courses and books. Interact with our community. One email per week, no spam; unsubscribe at any time