The philosophy of Maker Education

The philosophical foundations of the Maker Movement and the Maker educational style can be found in the writings of great philosophers. Aristotle was among the first to recognise the link between education and quality of life. Students, according to John Dewey, should be able to interact with and experience their curriculum.

Constructionism, developed by Seymour Papert, widely regarded as the father of the Maker Movement, was influenced by Jean Piaget's constructivism. According to constructivism, a learner constructs a personal understanding and learning of the world through their experiences.

Maker education revolution

Conventional education is struggling to provide the learning environment necessary to help raise the future innovators, problem solvers, and entrepreneurs that advanced societies need. Maker Education offers a model for education in the 21st century.

“If a child can’t learn the way we teach, maybe we should learn the way they learn.”

— Ignacio Estrada

The philosophical underpinnings of the Maker Movement and the Maker style of education can be traced in the writings of ancient philosophers, like Aristotle. Aristotle spent a large portion of his life thinking about education and learning. Although not a maker himself in the modern sense of the word, Aristotle was perhaps one of the first to recognise the relationship between education with quality of life. He is credited with having said that “the fulfilled person was an educated person”.

Aristotle also emphasised that learning must be balanced, with play, physical training, music, debate, science and mathematics all playing a role in developing healthy minds and bodies. He pointed out that learning is lifelong and best done by doing (1):

“Anything that we have to learn to do we learn by the actual doing of it... We become just by doing just acts, temperate by doing temperate ones, brave by doing brave ones.”

In more recent centuries, philosophers and educators have worked diligently in trying to understand learning and education in a modern context, as these are shaped by the industrial education paradigm.

John Dewey, an American philosopher and reformer, has greatly influenced the thinkers that eventually shaped the Maker Movement. He believed that students should and in fact must be allowed to interact with and experience their curriculum, and that they should be encouraged to take active part in their own learning.

“Give the pupils something to do, not something to learn and the doing is of such a nature as to demand thinking; learning naturally occurs”

— John Dewey.

Dewey is perhaps one of the first, if not the first, modern educator who argued that education should strike a balance between the delivery of knowledge and the wants and personal needs of the student. At that point, in the late 1800s, students were merely the recipients of facts and figures delivered by teachers across the classrooms of the developing and industrialising world.

Dewey became a proponent of hands-on learning and experiential education, which is related to experiential learning. Experiential learning is the process of learning through doing and reflecting on doing. On the other hand, experiential education involves both a teacher and a student and is described as the process of learning via the direct experience of the learner within the learning environment and the content.

All this was refined into concrete terms by later educators and practitioners. Seymour Papert, widely acknowledged as the father of the Maker Movement, developed constructionism. Constructionism is the theory of learning which arguably best explains the efficacy of Maker-style Education.

Papert’s constructionism is, in turn, heavily influenced by Jean Piaget’s theory of constructivism. In constructivism, a learner will construct a personal understanding and learning of the world through their experiences and their reflection on those experiences. In constructivism, passive learning does not lead to a real learning experience, only to a memorisation of facts.

A student of Piaget, Seymour Papert, through his constructionist approach, created a framework that can be used to apply Piaget’s core constructivist ideas. According to Papert’s constructionism, students learn by applying what they already know in practical projects designed to expose them to new knowledge. The role of the teacher is that of the coach. Step-by-step guides and lectures can be used as learning tools where it makes sense, but they are not necessary. In Maker-style education, the critical component in constructionism theory is that according to the theory, the student will learn best if they actively create tangible artefacts in the real world.

This is Papert’s definition of constructionism (2):

“The word constructionism is a mnemonic for two aspects of the theory of science education underlying this project. From constructivist theories of psychology we take a view of learning as a reconstruction rather than as a transmission of knowledge. Then we extend the idea of manipulative materials to the idea that learning is most effective when part of an activity the learner experiences as constructing a meaningful product.”

Papert demonstrated his theory by creating educational tools, some of them still in use today. He was one of the first educators to advocate the use of computers by students for the purpose of learning anything, not just computing.

This was in the 1960s, the very early days of computing. In those days, computers cost more than a car, and were used by specially trained technicians or scientists on specific academic and commercial applications. Papert suggested that children should be allowed to play with these machines, and should be encouraged to connect them to external appliances like lights and door locks. The children could then write programs and create interfaces to programmatically control appliances from the computer. This was the precursor of what today we recognise as “physical computing”, in which microcontrollers like the ones embedded in the Arduino prototyping platform, allow people to experiment with interfacing computers with the world around them.

Over the years, Papert developed various educational technologies that connected the computer programs and software with the physical world or treated computer science and algorithm design games. All this was designed to help learners learn through experience.

For example, the Logo programming language was developed in his MIT lab. In Logo, the learner can write a simple program to control a turtle icon on the screen. The turtle leaves a trace behind it as it moves around the screen, which eventually can become an elaborate drawing. The learner can see the result of an instruction in the program immediately on the screen and use that as instant feedback that can be used in the process of improving or extending the program.

Papert also created a physical turtle, the “Logo Turtle”, that exists in the real world in the form of a small robot. The movement of this robot can be controlled by the same program as its virtual counterpart. Logo Turtle is fitted with a collar marker so that it can draw a line on a sheet of paper as it moves on the paper’s surface. With the physical version of the turtle, learners can study robots and transfer their knowledge from the more abstract world of bits and bytes to that of atoms. Logo was developed in the 1960s, to make it fun for children to play with computers, and is still in use today as one of the oldest high-level programming languages.

Papert worked directly and indirectly on several other impactful projects, always informed by the principles of constructionism. For example, Lego’s Mindstorms robotics kits have been heavily influenced by Papert’s work, and even bear the name of his important 1980 book, Mindstorms: Children, Computers and Powerful Ideas.

In this book, Papert explains how “the child programs the computer and, in doing so, acquires both a sense of mastery over a piece of the most modern and powerful technology and establishes an intimate contact with some of the deepest ideas from science, from mathematics, and from the art of intellectual model building.”

Lego Mindstorms is a robotics educational platform that children use today in classrooms and homes across the world to learn how to build and control robots while they play. They are a colourful and engaging way to learn skills that traditionally require tedious and long study in a classroom environment.

Maker Education is essentially an education paradigm by which learners learn by exploring their own curiosities, and by using real-world artefacts to construct and reflect on their learning. In the remaining chapters in the section of this book we take a closer look at what this means in practically.

References

- Aristotle Nicomachean Ethics, Book II, p.91.

- Sabelli, N. (2008). Constructionism: A New Opportunity for Elementary Science Education. DRL Division of Research on Learning in Formal and Informal Settings, 193-206. Retrieved from http://nsf.gov/awardsearch/showAward.do?AwardNumber=8751190

Interesting readings

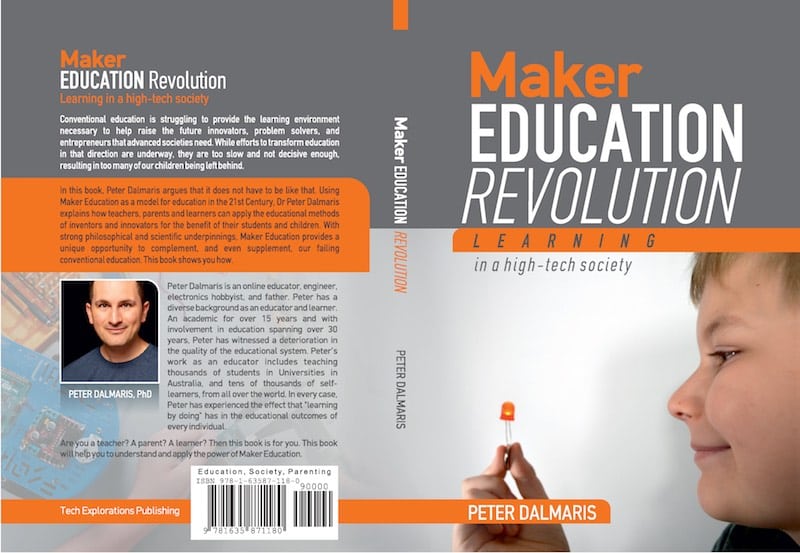

Maker Education Revolution

Learning in a high-tech society.

Available in PDF, Mobi, ePub and paperback formats.

Using Maker Education as a model for education in the 21st century, Dr Peter Dalmaris explains how teachers, parents, and learners can apply the educational methods of inventors and innovators for the benefit of their students and children.

Jump to another article

1. An introduction

2. A brief history of modern education

An education in crisis, and an opportunity

3. An education system in crisis

4. Think different: learners in charge

5. Learning like an inventor

6. Inventors and their process of make, test, learn

7. Maker Education: A new education revolution

What is Maker Education?

8. The philosophy of Maker Education

9. The story of a learner in charge

10. Learners and mentors

11. Learn by Play

12. Deliberate practice

13. The importance of technology education

14. The role of the Arts in technology and education

15. Drive in Making

16. Mindset in Making

Maker Education DIY guide for teachers, parents and children

17. Learning at home: challenges and opportunities

18. Some of the things makers do

19. The learning corner

20. Learning tools

21. Online resources for Maker learners

22. Brick-and-mortar resources for Maker learners

23. Maker Movement Manifesto and the Learning Space

An epilogue: is Maker education a fad or an opportunity?

24. Can we afford to ignore Maker Education?

25.The new role of the school

Last Updated 1 year ago.

We publish fresh content each week. Read how-to's on Arduino, ESP32, KiCad, Node-RED, drones and more. Listen to interviews. Learn about new tech with our comprehensive reviews. Get discount offers for our courses and books. Interact with our community. One email per week, no spam; unsubscribe at any time